I was thrilled to find out I’d won a Stephen Copley Award to support a research trip to Belfast. As part of a wider project tracing the influence of Anna Barbauld’s educational works on Dissenting women teachers working in differing geographical and cultural contexts, I was keen to explore archives relating to Belfast presbyterian educationalists Martha McTier (1742 – 1837) and Mary Ann McCracken (1770 – 1866). I hoped to find evidence of Barbauld’s influence in their writings, which might illuminate how their pedagogical projects engage, interpret and reframe Romantic-period political and ethical discourses.

Belfast was shining in unexpected January sun when I arrived outside Clifton House. Under a piercingly blue sky, the former Poor House’s Georgian windows welcomed light in. The building was designed by Mary Ann McCracken’s uncle, Robert Joy, who was firmly embedded in a Belfast Presbyterian community known for its expansive ethics and egalitarian politics. It’s therefore no surprise that the capacious curve of the steps leading into the building broadens outwards, as if to welcome all, and the entrance hall is flooded with light.

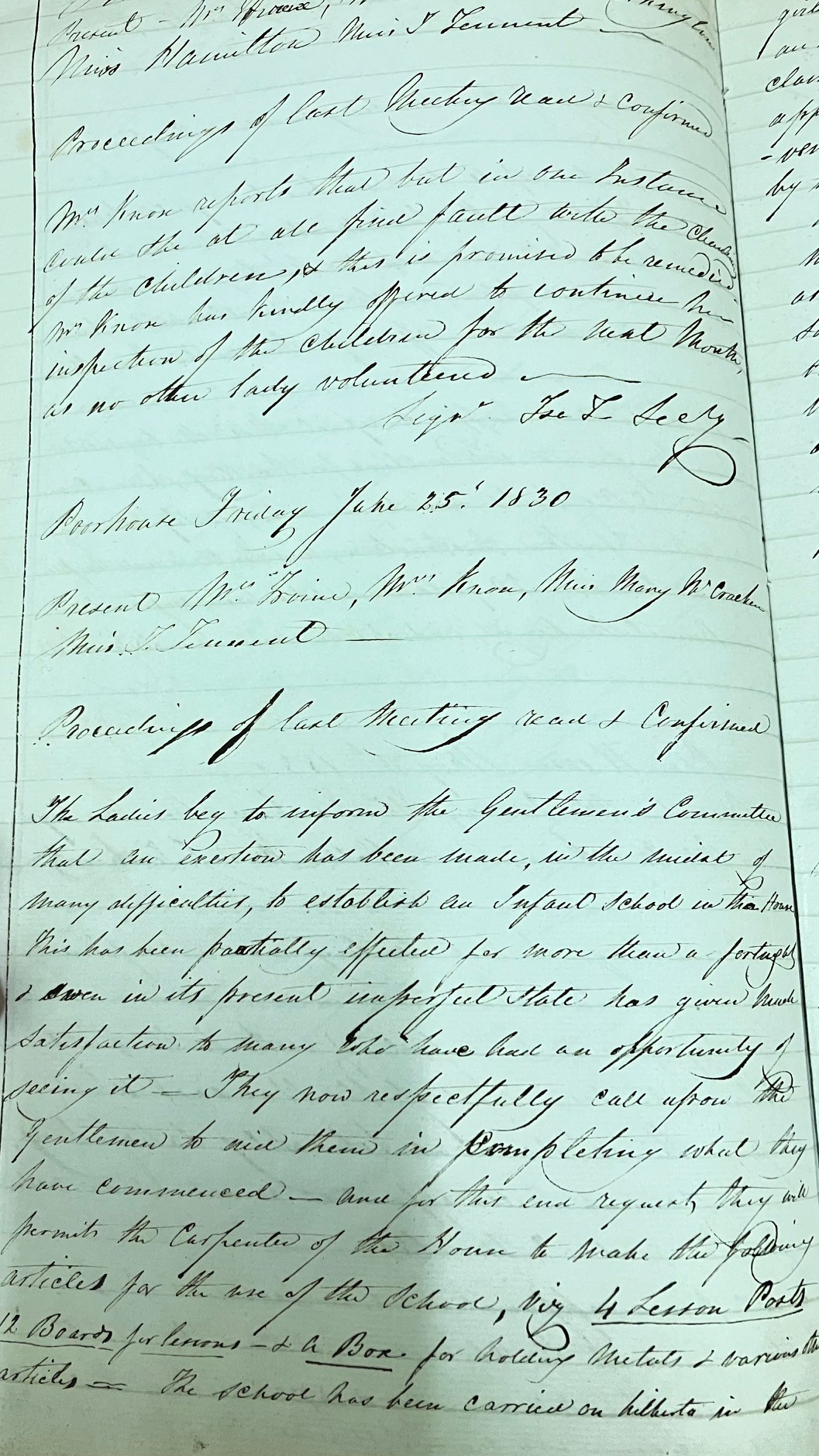

My appointment was with the Ladies’ Committee Book. Immaculately kept, the book itself reflects the dedication of the committee of Belfast women who, from 1827 to 1851, fought for basic human dignity and the means to create a positive future for women, girls and infants who called the Poor House their home. I was particularly interested in any details which might reveal evidence of Barbauld’s educational philosophy amongst records of the Ladies’ Committee’s fight to establish and run an infant school (against the wishes of the Gentlemen’s Committee). I found intriguing references to ‘reading lessons’ (echoing Barbauld’s seminal reading primer Lessons for Children). In addition, requests for playground equipment reflect the kinaesthetic approach to pedagogy Barbauld advances, for example in Hymns in Prose for Children: ‘every day we are more active than the former day’ (Barbauld,1781). In a very Barbauldian comment, McCracken insists that the children must be taken on walks, so that they might first experience objects before reading about them – typical of Barbauld’s associationist theory.

I was spellbound by what Clifton House’s records revealed about the care and attention McCracken and her committee devoted to ensuring the education, safety and holistic wellbeing of the young people in their care. Not content to simply organise apprenticeships for the girls, the committee arranged a visiting rota to ensure each girl’s ongoing welfare. Unsurprisingly, the records show that when it was McCracken’s turn, she never managed to get round all of her visits in a month, due to the length of time she spent with each girl. McCracken’s recurring requests for an extra month to complete her visits – in addition to her consistent demands for more soap – represent a poignant testimony to her dedication.

From Clifton House, I walked into the city centre, where Mary Ann McCracken’s contribution to Belfast has finally been recognised in a new statue. In the grounds of the city hall, McCracken looks out over the city, not so much proffering the abolitionist pamphlet she holds in her hand, as driving it forward. For me, this gesture says it all.

Formed in 1791 and disbanded after a failed rebellion in 1798, the Society of United Irishmen was characterised by its non-sectarian approach and outward-looking, cosmopolitan ethics. Drawing on transnational discourses of universal equality and rights, United Irishmen – and women – such as McCracken and McTier – agitated for equal representation, Catholic emancipation and an Irish republic. In the archives at Queen’s University, Belfast, I found a copy of 1790s activist Edward Hay’s History of the Insurrection of the County of Wexford, A.D. 1798. The title page is autographed ‘Mary Ann McCracken’: a reminder that McCracken’s involvement in the United Irish movement was not merely personal, as a sister of United Irish leader Henry Joy McCracken, but reflected her own political interests.

During my time in Belfast, I was lucky to meet with eminent scholar and Mary Ann McCracken expert, John Gray. In the wonderfully hospitable and architecturally gracious surroundings of the Linen Hall café, we discussed how Mary Ann’s status as a ‘whole-hearted revolutionary’ has for so long been obscured by a focus on her role in Henry Joy McCracken’s story (Gray, 2020). Our conversation uncovered fascinating leads to follow, especially to investigate Francis Hutcheson as a formative influence shared by disparate figures my project considers, to examine their participation in cross-denominational/non-sectarian projects as a theme that emerges from their work and to look more closely into their relationships to the revival and study of vernacular languages, music and cultures.

A real highlight of my time in Belfast was the privilege of handling original hard copies of the 1790s United Irish newspaper, the Northern Star. The Northern Star’s masthead bears the words ‘The Public will be Our Guide, The Public Good Our End’, boldly proclaiming the paper’s radical politics. I was keen to investigate a conversation that played out between 1795 and 1796, around the establishment of a ‘Union School’ for poor girls (Kennedy, 2025). As Secretary to the Belfast Humane Female Society, behind the establishment of the school, Martha McTier was central to this project, and by her own admission, wrote at least one of the pieces which appear in the Northern Star. In response to heavily sarcastic articles by anonymous contributors styling themselves ‘The Bucks’, the committee defend their decision to establish a school for girls, and more particularly, to run it as a boarding school. With synergies to McCracken’s practical philanthropy and Barbauld’s whole-child approach to pedagogy, the author (pseudonym Marcia) of a piece dated 25th April 1795 emphasises the importance of a school in which ‘female children should be instructed’ but also ‘fed and clothed’.

A piece by ‘Angelique’, published on 17th April 1795, has the ring of Martha McTier’s incisive style. With a rhetorician’s instinct, ‘Angelique’ sets out to shock, opening a paragraph with the statement: ‘We wish to know the faults of our scholars’. Unfolding her argument with inexorable logic, the writer channels Barbauld and Wollstonecraft in equal measure. She insists that the school’s purpose must be ‘to impress upon [the girls’] minds a reverence for themselves which ensures that of the world’. This statement recalls Barbauld’s tenet that children must first ‘reverence’ their own minds in order to flourish in society, and Wollstonecraft’s insistence that women should seek power ‘over themselves’, through education (Barbauld,1781; Wollstonecraft, 1792).

From the Newspaper Office, I explored a maze of close-walled ‘Entries’, where United Irish ideals were consolidated and contested in the 1790s. Walking down ‘Wilson’s Court’ in encroaching darkness, it wasn’t difficult to conjure the ‘fug of testosterone’ Claire Mitchell envisages filling the pubs that lined these narrow alleyways (Mitchell, 2022). I stopped to admire a mural that marks the site of the Northern Star press, relishing the idea that through the power of print, Martha McTier’s stridently worded article(s) in support of girls’ education, regardless of wealth, religion or class, claimed their place at the heart of this ostensibly testosterone-fuelled milieu, in the pages of the Northern Star.

Martha McTier was deeply involved in United Irish networks – so much so that she regularly included asides to the Belfast postmaster in her letters, who she knew was censoring her correspondence with her brother, United Irish founding member Thomas Drennan. McTier was also an educationalist – in her view, the practices of pedagogy and politics were interconnected. As Catriona Kennedy notes, McTier’s students, in the small school she kept in her home, did not ‘gabble from the testament only’: she taught them to read the political affairs of the day, from the newspaper: ‘four of them can read Fox and Pitt’ (Kennedy, 2025).

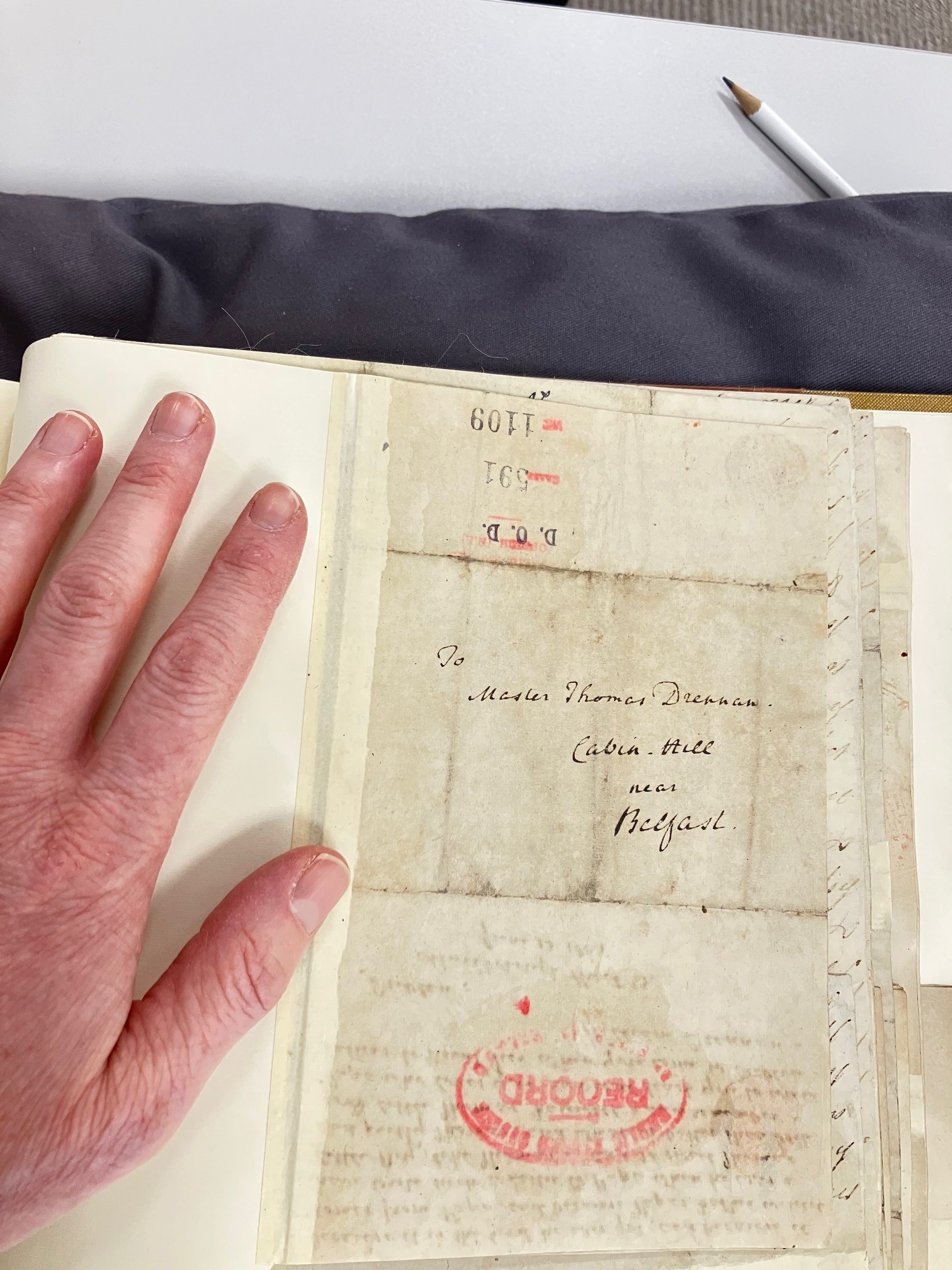

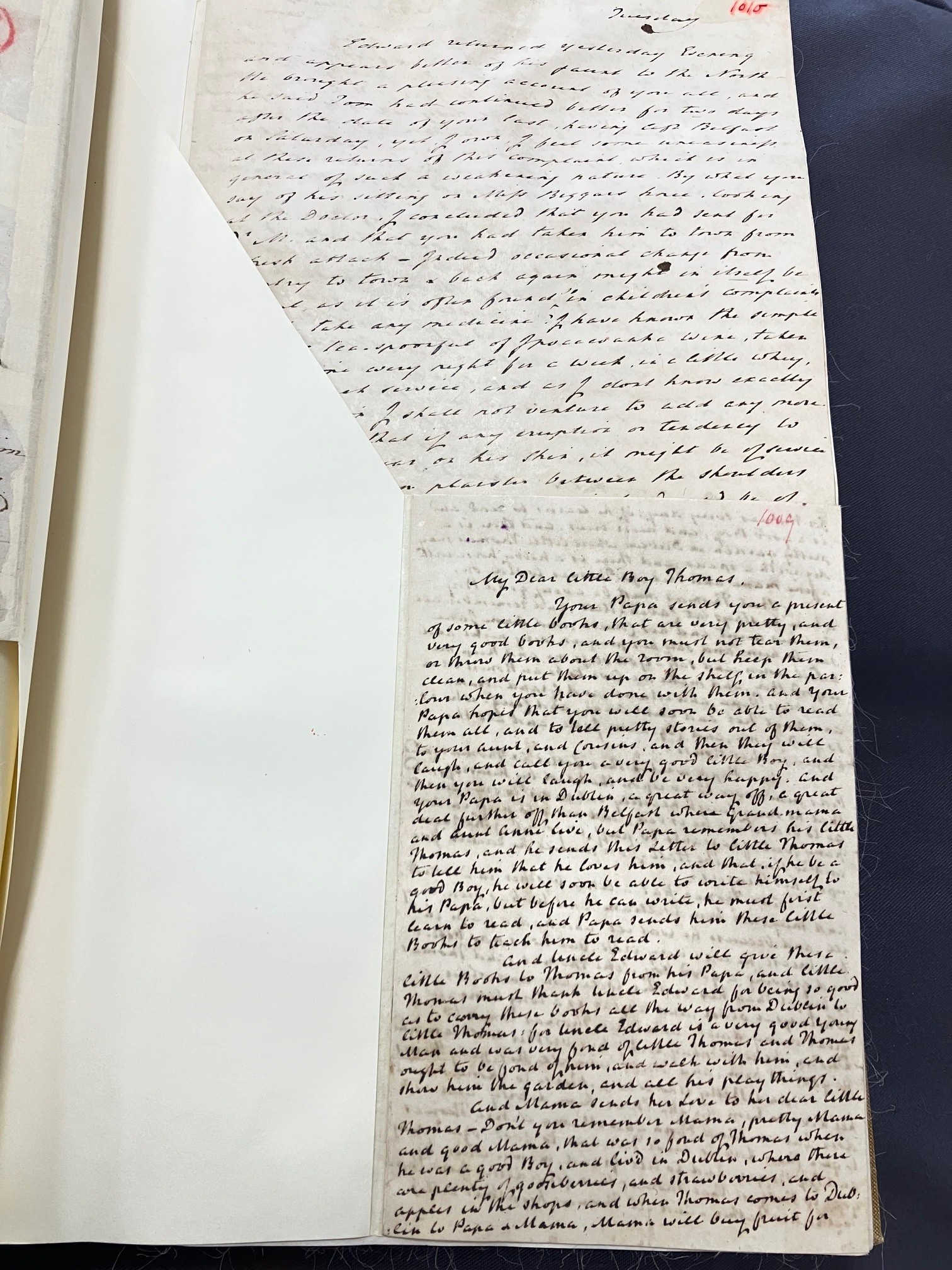

Significantly for my research, I have discovered that Martha McTier also used Barbauld’s Lessons for Children to teach her students to read and write, and read Barbauld with her own nephew, Tom. I visited the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) to examine some letters between McTier, Drennan, and her nephew Tom in manuscript. I was interested to examine whether McTier and Drennan engaged Barbauld’s pedagogical approach in the style and format of their letters to this young child, who spent much of his time living with McTier. I was delighted to discover that they did! Their letters to Tom were adapted, as were Barbauld’s books, to the dimensions of a child’s hand and, compared to the scrawl of their letters to each other, the handwriting is very clear. Unremarkable on their own, taken together with McTier’s use of Barbauld’s books to teach Tom to read, her advocation of a ‘Barbauldian’ childhood in sending Tom out ‘into the fields’ around her home at Cabin Hill and building an affectionate, tactile relationship similar to that modelled by ‘Mamma’ and ‘Charles’ in Barbauld’s books, a picture emerges of an educational approach pervaded by Barbauld’s influence on every level.

As a treat on my final day, I booked myself on to a ‘Mary Ann McCracken and Martha McTier’ walking tour. It was refreshing to get my head out of the archives and explore the city, visiting some of the places which held significance for these remarkable women. Walking in their footsteps, I felt inspired to capture the continuing vitality of their contribution to Ulster history. I’m so grateful for the opportunity to undertake this research trip, and I look forward to sharing my findings at the BARS Conference in July.

Jenny Tattersall is a PhD student at Newcastle University. Her project ‘Daughters of Dissent: Citizens of the World? Anna Barbauld, Dissent and Radical Atlantic Pedagogy, 1778 – 1837’ traces Barbauld’s influence on Dissenting women educationalists writing from Ireland, West Africa, the Caribbean and North America. Her AHRC Northern Bridge DTP-funded research locates pedagogy at the centre of Romantic-period transatlantic discourses of human rights, embedded in Dissent and actualised by women.

Image permissions:

Northern Star image: c. Libraries NI

Letters addressed to Tom Drennan: c. the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland PRONI, D591/1/13/1109